Trapped by Debt: Why the Energy Transition Will Stall Without Fiscal Justice

Blog by Paula Rosa Haerle, MSc Comparative Politics

13 October 2025

This paradox captures the central concern of the research I conducted as part of my master’s thesis: the growing tension between climate transition goals and the fiscal realities of Sovereign External Debt. Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are asked to leave fossil fuels underground while simultaneously being locked into repayment schedules and fossil fuel dependence. The urgent question is not simply whether these countries want to transition, but whether debt structures allow them to.

Extending Carbon Lock-in Theory

My thesis develops the concept of Debt-Driven Carbon Lock-in. Whereas carbon lock-in theory has shown how infrastructures, institutions, and technologies create path dependency in fossil fuel economies, little attention has been paid to the role of debt in sustaining fossil fuel dependency. Using quantitative data analysis and expert interviews, I aimed to map out mechanisms highlighting how sovereign external debt is not merely a constraint in the background, but an active driver that deepens fossil dependency.

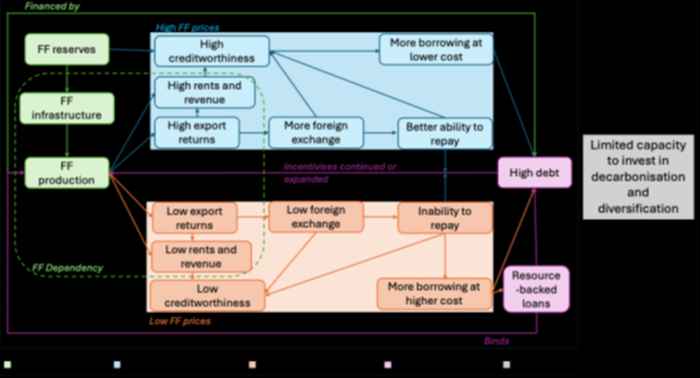

These mechanisms illustrate a broader circular dynamic:

Debt servicing requirements push states towards fossil extraction, and reliance on fossil revenues deepens vulnerability to commodity cycles, generating new rounds of borrowing (Figure 1). Debt and fossil dependence, thus, reinforce each other in ways current transition debates rarely recognise.

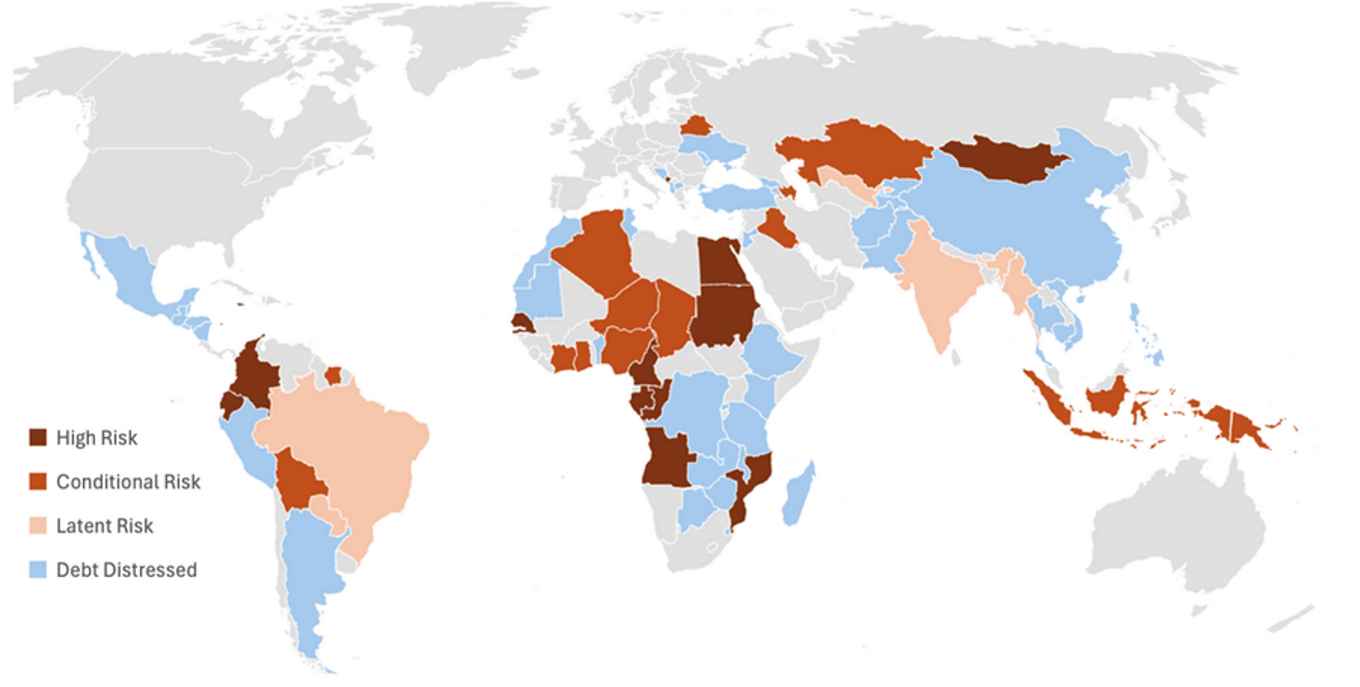

Mapping Structural Exposure

To substantiate this claim, I developed two composite indices:

- The Fossil Fuel Dependency Index (FFDI), which captures structural reliance on fossil fuels through export concentration, fiscal gain and dependence; and

- The Sovereign External Debt Distress Index (SEDDI), which measures the fiscal pressure Sovereign External Debt imposes on fossil fuel-producing LMICs compared to general GDP, exports and government revenue.

By combining these indices, I identified 31 LMICs where high fossil fuel dependency overlaps with high debt distress. These states face a heightened risk of debt-driven lock-in. The indices are not predictive models but heuristic tools: they map exposure and structural vulnerability rather than destiny or recognised distress. The pattern shows that the debt–fossil fuel trap is not confined to one region but spans Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, and Asia, underscoring its global scale (Figure 2).

Mechanisms of Debt-Driven Lock-in

The global mapping and expert interviews point to five main mechanisms through which debt entrenches fossil dependency:

- Revenue volatility and procyclical borrowing: Debt spikes when fossil prices fall, forcing renewed extraction to stabilise budgets.

- Presource borrowing: loans are taken against anticipated fossil revenues, creating pre-emptive commitments to extract.

- Budgetary dependence: Debt service obligations prioritise fossil exports as the quickest route to foreign exchange.

- Debt-financed infrastructure and contracts: Instruments such as resource-backed loans and investor–state dispute settlement (ISDS) clauses hardwire fossil production into legal and financial frameworks.

- Crowding-out of alternatives: Debt distress reduces fiscal and credit space for renewable investment, making diversification harder.

Together, these mechanisms show how debt is not incidental to fossil lock-in, but it actively sustains and reproduces it.

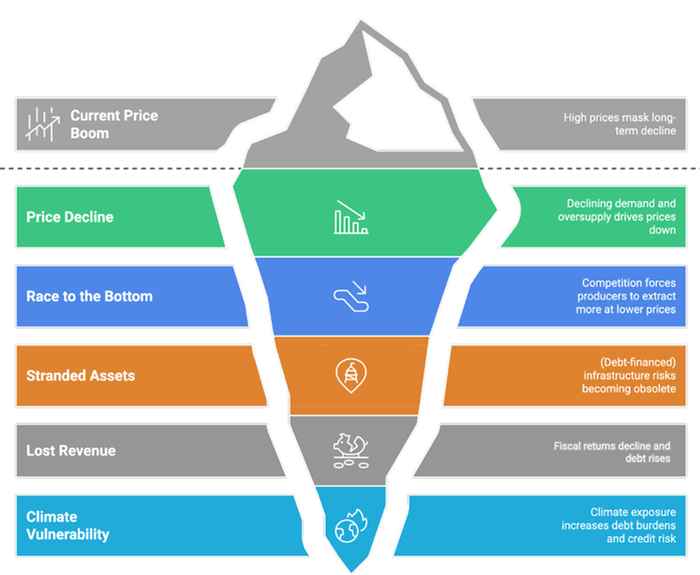

Implications for the Energy Transition

These findings highlight a fundamental incoherence in global climate governance. International negotiations often assume that fossil phase-out is a matter of political will or technological readiness. Yet for many debt-distressed LMICs, “long-term planning becomes a luxury”, as one interviewee put it.

In this context, the asymmetry is stark. A diversified high-income petrostate can finance transition pathways through capital markets; a debt-stressed exporter, already devoting half of government revenue to debt service, cannot. Current approaches that treat these actors as if they face similar choices risk entrenching injustice and slowing the global transition.

Conclusion

My thesis contributes to carbon lock-in theory by integrating sovereign external debt as a core mechanism of fossil entrapment. The central conclusion is that debt-driven carbon lock-in limits both the possibility and the pace of transitions in structurally exposed LMICs.

If international debates continue to overlook debt, they will misdiagnose why fossil extraction persists. Keeping fossil fuels in the ground requires more than political commitment but confronting how debt structures channel states towards extraction and away from transition. Until those structures are addressed, debt-distressed producer states will be locked out of global energy transitions, facing long-term consequences of entrenched fossil fuel dependence, deepening debt distress, and an exclusionary, slow transition that disproportionately harms the very countries most structurally exposed.

By Paula Rosa Haerle, MSc Comparative Politics

This blog post is based on my Master’s thesis in Comparative Politics at the University of Amsterdam. The research was conducted as part of the Climate Change and Fossil Fuels (CLIFF) research project funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Adv. Grant No 101020082). All views expressed are my own.